Understanding the Complex Morality of Japanese Fairy Tales: Kachikachi yama

- Tian Gao

- Aug 27, 2025

- 5 min read

In 2015, NHK released Fairy Tale Tribunal (Mukashi banashi hōtei 昔噺法廷), an educational TV series that put beloved characters from traditional Japanese fairy tales under legal scrutiny. Heroes who were long celebrated were now being accused of immoral behavior like revenge, violence, and dishonesty. This fresh look blurred the lines between good and evil, urging viewers to reconsider long-held moral views. One such tale examined in the series was Kachikachi yama (かちかち山, “The Cracking Mountain”).

While today’s version of Kachikachi yama is a story of redemption and forgiveness, its older versions offer a much darker take, filled with violence and retribution. This post explores how Kachikachi yama has evolved over time and what these changes reveal about the moral lessons in Japanese fairy tales.

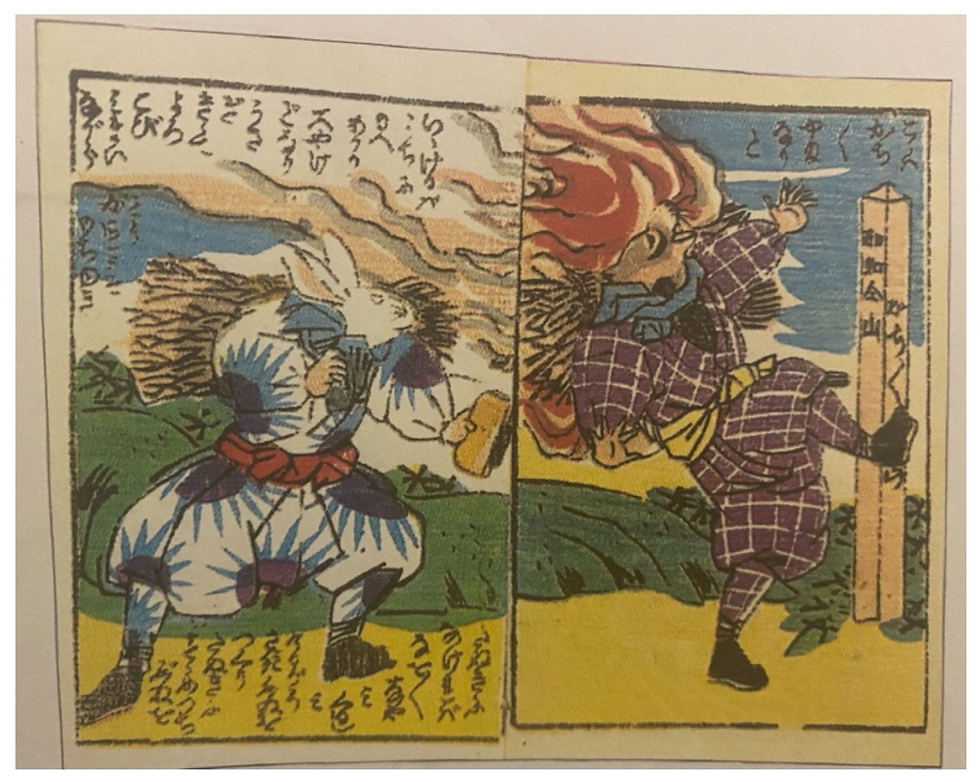

In the modern version, Kachikachi yama tells the story of a tanuki (Japanese raccoon dog) who steals food from an old man’s farm. The old man captures him and plans to cook him, but the tanuki tricks the man’s wife into setting him free. After escaping, the tanuki beats the old woman. In revenge, their friend, a rabbit, helps the couple by tricking the tanuki: first burning his back, then applying spicy miso to the burns, and finally sabotaging a mud boat, causing the tanuki to drown. In the end, the tanuki repents, and forgiveness is granted, leading to a happy ending.

At first glance, the moral lesson seems clear: laziness, theft, and violence are wrong, and those who repent should be forgiven. However, the rabbit’s deceptive and violent actions complicate this message. While the rabbit is positioned as the hero, his dishonesty and cruelty are celebrated, adding layers of moral ambiguity. Such moral ambiguity might puzzle scholars of children’s literature and the sheer amount of violence portrayed in this story might also be seen as controversial. Some believe children can navigate such ethical dilemmas, while the majority argue young readers need clearer guidance, especially when violence is presented as justifiable.

Interestingly, the contemporary version of Kachikachi yama is much more sanitized. In older versions, especially before the 1940s, the tale was far darker. Its roots can be traced back to oral folktales of the late Muromachi period (1392–1573) and Edo period (1600–1867), when it was first recorded in picture book form. These older versions had striking differences:

Two Murders: In older versions, the tanuki kills the old woman, and in turn, the rabbit kills the tanuki in a violent act of revenge.

Cannibalism: The tanuki disguises himself as the old woman, cooks her into a soup, and serves it to the old man, who unknowingly eats his wife!

No Forgiveness: Unlike the modern version, there’s no apology or redemption for the tanuki; the story ends with his violent death.

These elements present a much more complex moral narrative, particularly around themes of revenge and justice.

Revenge as Righteous?

In the older versions, revenge plays a central role, and the rabbit’s actions are portrayed as morally righteous. This reflects early-modern Japanese values, particularly the practice of kataki-uchi (敵討ち, “lethal vendetta”), where revenge for a murdered family member or master was considered a virtuous duty. Under Tokugawa law, such vengeance was legally permitted and seen as an act of loyalty and filial piety. The rabbit’s revenge for the old couple, who act as parental figures, aligns with this ideology. In contrast, the tanuki’s retaliation is selfish, making his violence unacceptable by these moral standards.

Good and Evil: Not So Simple

What’s fascinating about Kachikachi yama is how it challenges notions of good and evil. While the rabbit is seen as the hero and the tanuki as the villain, the story complicates this binary. The rabbit carries out his revenge with cold precision, hiding his emotions from readers, making it hard to connect with him personally. In contrast, the tanuki’s suffering is depicted in vivid detail. In one gruesome scene, the rabbit sets fire to the tanuki’s back, watching him writhe in pain. The tanuki’s screams, described in detail, may evoke sympathy, even from child readers, complicating the view of him as purely evil.

Furthermore, the old couple are not as innocent as they appear. They are shown plotting to kill and eat the tanuki, which is significant given that meat consumption was forbidden in early modern Japan and viewed as sinful in both Buddhism and Shintoism. Although this taboo lessened during the Meiji period, killing an animal for meat was still seen as questionable. The old man’s later enjoyment of soup made from human flesh—after unknowingly eating his wife—further taints their innocence, blurring the line between villain and victim.

What Do These Changes Tell Us?

The transformation of Kachikachi yama from a violent tale of revenge to today’s more forgiving version reflects changing ideas about childhood and morality in Japan. During the Edo period, children were often viewed as “little adults” who needed to be exposed to the harsh realities of life, and stories like Kachikachi yama didn’t shy away from violence and revenge. In contrast, today’s version of the story focuses on redemption and forgiveness, teaching that those who repent can change for the better.

This shift raises important questions about the role of fairy tales in children’s literature. Should fairy tales shield children from the darker aspects of life, or should they prepare them for it? Should stories teach simple moral lessons, or should they introduce children to more complex ethical dilemmas?

Works Cited

Kachi kachi yama かちかち山, Edo: Satō Shintarō 佐藤新太郎, 1885. Critical edition in Bakumatsu Meiji mamehon shūsei 幕末明治豆本集成, edited by Katō Yasuko 加藤康子, 218–222. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai 国書刊行会, 2004.

Kachi kachi yama かちかち山. Moriya Jihee 森屋治兵衛, n.d. Critical edition in Bakumatsu Meiji mamehon shūsei 幕末明治豆本集成, edited by Katō Yasuko 加藤康子, 24–29. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai 国書刊行会, 2004.

Kachikachi yama かちかち山. Hirada Jōgo 平田昭吾, Tokyo: Nagaoka shoten 永岡書店, 1993

Katō Yasuko 加藤康子. Bakumatsu Meiji mamehon shūsei 幕末明治豆本集成. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai 国書刊行会, 2004.

Krämer, Hans Martin. ‘“Not Befitting Our Divine Country’: Eating Meat in Japanese Discourses of Self and Other from the Seventeenth Century to the Present.” Food and Foodways 16, no. 1 (14 March 2008): 33–62.

Mills, D. E. “Kataki-Uchi: The Practice of Blood-Revenge in Pre-Modern Japan.” Modern Asian Studies 10, no. 4 (October 1976): 525–542.

Moretti, Laura. Recasting the Past: An Early Modern Tales of Ise for Children. Leiden; Boston: Brill Academic Pub, 2016.

Nikolajeva, Maria. “Guilt, Empathy and the Ethical Potential of Children’s Literature.” Barnboken 35, no. 1 (2012):1–13https://doi.org/10.14811/clr.v35i0.139.

Nikolajeva, Maria. Reading for Learning: Cognitive Approaches to Children’s Literature. Children’s Literature. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2014.

Nussbaum, Martha Craven. Poetic Justice: The Literary Imagination and Public Life. Boston: Beacon Press. 1995.

Williams, Kristin. “Childhood in Tokugawa Japan.” In The Tokugawa World, edited by Leupp, Gary P and De-min Tao, 249–279. New York, NY: Routledge, 2021.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Tian Gao is a third year Ph.D. student in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. She nurtures a keen interest in Japanese early modern woodblock, copper prints, miniature size picturebooks (mamehon 豆本) and Pastoral tradition.

She is currently researching Japanese children’s reading materials from the second half of the nineteenth century, focusing on cognitive perspectives. Her work challenges the common belief that Japan lacked children’s literature before the Meiji period (1868-1912), when Western philosophical concepts of childhood were introduced. Her project aims to uncover a uniquely Japanese understanding of childhood, independent from Western influence, by examining materials that predate the emergence of modern concepts of childhood in Japan.

Comments