An Interview with Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom/정울림, Graphic Artist and Author

- Sarah Park Dahlen

- Jun 17, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Jun 8, 2023

In 2019, I spoke on a panel about representations of transracial adoption in youth literature for the IRSCL congress, which was themed “Silence and Silencing in Children’s Literature.” Having researched representations of adopted Koreans in youth literature, and having found that adopted persons have been silenced and spoken for in nearly all adoption discourse, the congress theme was the perfect venue for a panel about adoption. During the panel, my colleague Tobias Hübinette (a critical adoption and race scholar and a Korean adoptee) talked about a graphic memoir that had recently been published in Sweden. Palimpsest: Documents From a Korean Adoption, written and illustrated by Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom, was originally published in 2016 in Swedish and translated into English in 2019. I acquired and read it when I returned to the United States and have since both cited and assigned it in my Library and Information Science classes (Readers’ Advisory Services and Library Materials for Young Adults). Palimpsest tells Sjöblom’s story—her childhood as an adopted Korean in a white, Swedish family and society; her adolescence and struggles with depression; and her adulthood, including her marriage, parenting, and search for biological family in Korea. When the ChLA international committee asked if I would interview Lisa, I eagerly agreed. - Sarah Park Dahlen 박사라

This interview was held over Zoom and transcribed by Maria Becker (St. Catherine University MLIS Program graduate assistant). It has been edited for clarity.

SPD: Can you tell us briefly about your childhood including the kinds of children’s books you read as a child?

LWRS: I grew up in a tiny northern village in Sweden. I was far away from everything, which also

meant that I was very far away from other Koreans or any sort of Korean culture. At that time we didn’t have much of it in general in Sweden but we certainly didn’t have anything where I grew up—or even close to where I grew up. So in terms of the books I read, I was like any other Swedish kid—they were mostly about white people, and most of them were written by famous Swedish children’s authors which included problematic language and mostly white people, but I didn’t really think about it at the time. Because of that and also the way that adoptees are usually treated by their white families in Sweden’s colorblind culture, you don’t really learn to appreciate that you look different or to be proud of where you come from. It’s more of a sort of well-intentioned whitewashing. For example, people could say: “I don’t see you as Asian, I think of you as a Swede.” It’s well intentioned, but it also erases you completely.

I was also taught that adoption was beautiful, which Palimpsest deals with. I address it in the beginning of the book—how you talk about yourself through your parents’ story. I used to say that my parents couldn’t have children, but that’s not true because my parents did have children—they had me, and then my next set of parents couldn’t have children so they adopted me.

SPD: What is Palimpsest about and why were you compelled to create it?

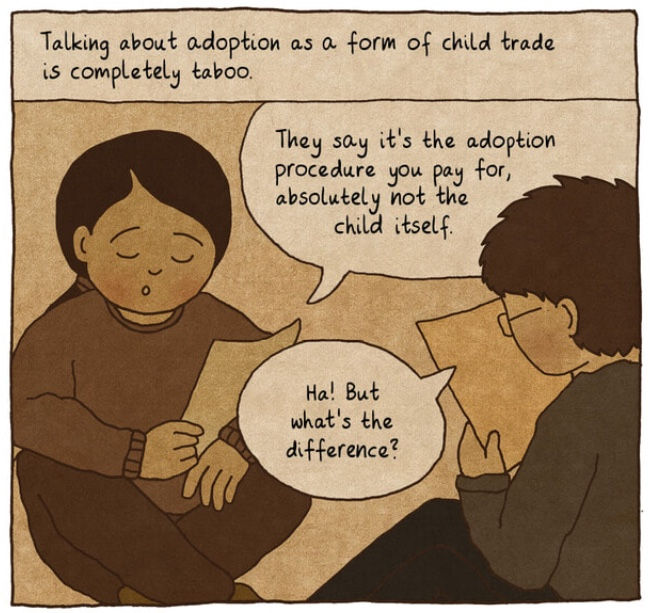

LWRS: I knew that I wanted to make a book called Palimpsest because I thought the word “palimpsest,” which is Greek, was the perfect metaphor for adoption. You have an original story that is erased and then replaced with a new story. If you keep digging in that word, its history and the history of palimpsests, you realize that there are so many layers that connect to the adoption narrative. I’ve always been writing and drawing stories, and I’d known for a long time that I wanted to do something about adoption. It started out as this really positive narrative, a bit comical. I started making comic strips about hilarious situations that you get into as an adoptee, like people asking if you’re bought, “ha ha ha, super funny,” and if you can get a refund if you don’t like the kid, and I saw this as sort of humorous.

I realized that I’d been duped my whole life into thinking that adoption is one sided—that it’s simple, that it’s beautiful, that it’s about rescuing and a win win win, so Palimpsest deals with the narrative that we are taught and how I start rethinking, relearning this, and then become a full blown activist. So I usually say that there are two stories, and that I use my search story to actually tell the story about how I deal with my view of adoption and learning that there is an industry, corruption and that so many adoptees are suffering. But I also felt that it needed to be written because of the lack of adoptee voices in general. And in particular adoptee voices that don’t just repeat everything adoptive parent narratives say – because there have been books by adoptees as well, but they are generally also part of the happy narrative. So when people say that adoptee voices have been silenced, it’s not entirely true; it’s more like adoptive adoptee voices who aren't singing the happy adoptee tune, they are the ones who are silenced.

SPD: What is your process for mapping out the story—does the text come first? Do the illustrations come first? Can you tell us how you thought about, wrote about, drew, and formatted Palimpsest?

LWRS: It was such a long process so I will talk about the bit that ended up in the book. The story came first because it was happening while I was writing it. Since I’d been working on it before I started my search—my second search—I had a lot of material already. So I was working on the book and then I started searching [again] and thought of writing about that. I often thought, “Ok, so my book is going to end with me not finding my mother.” And then something would happen, so I kept adding and adding. We also went back to Korea to meet her, so the book was writing itself while it was happening, which was quite extraordinary. When I was in Korea I Facebooked about it, and one of my friends who is an editor at Galago, who originally published Palimpsest, wrote to me and said “We would like to publish this book when you’re done with the manuscript because I can see that this is an incredible story.” So in that sense it was very easy to structure the whole book. The text came first, and I wrote the whole manuscript and showed it to my editor before I started drawing. When I make comics I usually get the images in my head while I’m writing. So when I started laying out the drawings for it, I already knew most of them, but just in my head. Also, when you work with comics, a lot of the things that you’ve written you end up erasing because you can say it with a drawing instead.

SPD: Your dedication says, “This album is dedicated to all adoptees living and dead whose voices have been silenced.” This was very compelling to me because the first time I learned about your work was during the 2019 IRSCL conference (in Sweden), which was themed “Silence and Silencing in Children’s Literature,” when I was on an adoption panel titled “Shattering Silences and Stereotypes in Transnational Adoption Narratives” with Shannon Gibney and our mutual friend Tobias Hübinette. What did you mean by this dedication?

LWRS: I was thinking about two things. One was that we are so silenced in the narratives about

us, and that’s one of the things that activists keep saying—that the most important voice in adoption is the one that's being silenced, which is the adoptee’s voice. And then I also thought about all the adoptees who have been silenced in their own lives—those who haven't been allowed to express what they feel or express who they are because it doesn't fit in with the idea of what adoption is. And how many of them have died because of this.

SPD: “Who owns the story of an adoption?” is one of the questions that you ask in your book. Can you say more about this?

LWRS: One of the things that shocked me when I started looking into adoption more was that adoptive parents and adoptees weren’t on the same side. I’d sort of assumed that we would be. I was just so sure that if I write about corruption they’re going to be shocked and horrified and want to join me in my activism, and then it turned out that they thought that I should be quiet because what I was saying was making things harder for them and their children. I also think that a big part of the adoption narrative belongs to the first parents who are often completely silenced. But I do think that when it comes to adoption, adoptees are definitely the ones who have the least choice, and our trauma lives on in our children. So I think that ours are probably the most important voices, but the more I hear about first mothers and things that have happened to them, I definitely don’t want to dismiss their voices either.

SPD: Can you tell us about the literary production of adopted Koreans or other transracially adopted people in Sweden? Both for adults and for child readers?

LWRS: There’s not much for children by adoptees. Most things written for children are by white adoptive parents. More and more stories by adult adoptees are published, mainly for young adults and adults, but many of them are self-published and of varying quality. There are not many of them that are critical, and my book is the only one that really deals with corruption and the structural problems with adoption, whereas most of the others are about reunions or focusing on an inward journey.

SPD: In Palimpsest you write about how adoptees are perpetually perceived and treated like children or even as infants. Can you say more about that?

LWRS: There are several levels to this. First of all the language—and I know that this is similar in English—people tend to say “adopted children,” rather than “adoptees.” In Swedish I use the word “adoptee”—I don’t know for how long it’s been used—but most people still say “adopted child.” I understand when it’s used properly, like “I am my parent’s adopted child,” but when I’m talking to you, for instance, if you kept asking me “As an adopted child, what do you think about...”, then I’d prefer to be addressed as an “adoptee” because I’m an adult. So we have that level where the language is preventing us from being seen as adults. And we’re constantly placed in the context of being children because that’s when the adoption happened, and then we also have the racist element that people tend to infantilize people of color.

Also, this doesn’t just happen with adoptees but also our first mothers. When I hear white adoptive parents talk about the first mothers it sounds like they’re talking about children. This is a serious problem because it feels like the conversation is always unequal at the starting point because I talk to adoptive parents who are ten, fifteen years younger than me and they address me as a child, while I address them as adults. They talk about themselves as parents and they talk about me as a child, and that means also that when we criticize things we are talked to as toddlers, like we are toddlers having a tantrum. You know, “Oh you’re being unreasonable, you're being hysterical, you're being upset, you're hateful, you're angry.” It’s hard to say what is what because I think that racism and our status as adoptees—all these things are linked together to turn us into perpetual children.

Additional Resources

Dahlen, Sarah Park. (2020, May 10). Silence, sorrow, and separation. Sarah Park Dahlen. https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2020/05/10/silence-sorrow-and-separation/

Gavaler, Chris. (2019, November 13). Sjöblom’s ‘Palimpsest’ is visually unlike most graphic memoirs. Pop Matters. Retrieved from https://www.popmatters.com/lisa-wool-rim-sjoblom-palimpsest-2641306882.html

Lathan, Tom. (2020, May 1). Holes in the soul: Childhood disorientation and rootlessness. TLS. Retrieved from https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/palimpsest-lisa-wool-rim-sjoblom-review-tom-lathan/

Navascués, Logaine. (2020, October 13). Palimpsest: Documents of a Korean Adoption, by Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom. Young adulting: Serious reviews of books for kids and teens. Retrieved from https://youngadulting.ca/2020/10/13/palimpsest-documents-of-a-korean-adoption-by-lisa-wool-rim-sjoblom/

Palimpsest. (2019, July 10). Publishers Weekly. Retrieved from https://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-77046330-1

Palimpsest: Documents from a Korean adoption by Lisa Wool-rim Sjöblom. (n.d.). Drawn and Quarterly. Retrieved from https://drawnandquarterly.com/palimpsest-documents-korean-adoption

Review of Palimpsest: Documents from a Korean adoption by Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom. (2020, July 18). Multiframe. Retrieved from https://multiframe.wordpress.com/2020/07/18/review-of-palimpsest-documents-from-a-korean-adoption-by-lisa-wool-rim-sjoblom/

Sjöblom, Lisa Wool-Rim. https://www.instagram.com/chung.woolrim/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom/정 울 림 is an illustrator, cartoonist, and graphic designer living in Auckland, New Zealand, with her partner and two children. She has a master’s degree in literature from Södertörn University and has studied at the Comic Art School in Malmö. Palimpsest is her first graphic novel. She is an adoptee rights activist.

Twitter: @chungwoolrim

Instagram: @chung.woolrim

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER: Sarah Park Dahlen is an Associate Professor in the MLIS Program at St. Catherine University. Her research is on Asian American youth literature and transracial Korean adoption. She co-created the Diversity in Children’s Books infographics and administered Lee & Low’s 2015 Diversity Baseline Survey. She co-edits Research on Diversity in Youth Literature and co-edited Diversity in Youth Literature.

Website: sarahpark.com

Twitter/Instagram: @readingspark

Comments