Disability, Death, and Temporality in Le Petit Prince and Thomas et l’infini

- Yvonne Medina

- Oct 24, 2023

- 4 min read

Content Warnings: Discussions of child death, disability, and suicide follow.

Thomas et L’infini has not been translated into English. All translations here are my own.

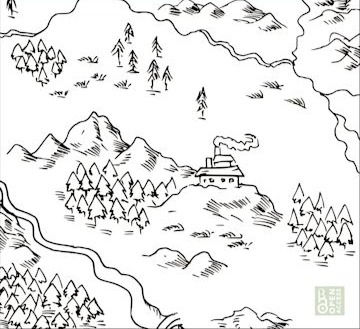

While Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince published in 1943 enjoys much scholarly attention, Michel Déon’s picture book adaptation, Thomas et L’infini (1975), lushly illustrated by Étienne Delessert, is far less well known. Thomas et l’infini, or Thomas and the Infinite in English, received the European Prize for Children’s Literature in 1976. A Gallimard Pocket edition with an educational supplement published in 1990 suggests it may have been used in French pedagogical contexts. Here, I point out how this understudied text grapples with some of the same temporal questions of the original such as whether children can access alternative temporalities that evade the fallen nature of adults. Both books feature hallucinations and spherical settings, an asteroid and a tropical island, where time flows cyclically in an endless stasis.

Thomas is slowly dying from an unnamed disease. He experiences fevers at night and only pretends to take his medication so he can go on long hallucinogenic journeys to a tropical island. This paradisical island populated with tame beasts remains a perfect Arcadia until Thomas meets a ghost named Maurice who refuses to answer his questions about infinity. Thomas wants to know what lies beyond the world he can perceive and, therefore, the limits of human understanding. He asks, “Where does infinity end? … What belongs to the stars and the suns, and worlds like ours that one sees in the sky? What lies beyond them?” (Déon 38, my translation). Maurice replies, “No one, not a single human being can withstand it. There does not exist a vast enough imagination to conceptualize infinity. Whoever could describe the infinite would no longer be a human” (Déon 38, my translation). Maurice holds a council with other ghosts, but only Death, here personified as a female angelic creature, can answer Thomas’ question. Thomas bravely decides to leave the ghosts behind and accompany Death so he can learn what lies beyond the finite. Thus, while The Little Prince follows a boy who lives alone on an asteroid and embarks on an interplanetary journey to Earth before perhaps returning to the asteroid after his suicide, Thomas et L’infini follows a somewhat reverse journey. Thomas moves from Earth to a tropical island dreamscape where he lives alone before dying and traveling beyond the finite.

In The Mighty Child: Time and Power in Children’s Literature, Clémentine Beauvais convincingly asserts that The Little Prince chronicles a movement from puer aeternus, the eternal child inherited from the Romantic era who exists in a cyclical, timeless childhood arcadia, to puer existens, the child of existentialist thought who is initiated into adult time. She describes angsty existential, adult time as vacillating uneasily between nostalgia, anxiety, and the present moment. Therefore, puer existens constitutes a fallen state of puer aeternus. The interaction of a child with someone else, or the intrusion of the other, initiates this shift from cyclical, childhood time to adult, existential time. The addition of another character disrupts the idyll and introduces self-consciousness, functioning like the snake in the garden of Eden.

Like Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, these boys live alone at first on their respective spheres with only animals for company. Thus, both books could be considered Robinsonades, stories that rewrite the Robinson Crusoe myth by situating a human on a deserted island. The deserted island can be theorized as a bubble or a representation of individual consciousness, demarcated from those of others. In Robinson Crusoe, Friday, the indigenous man Crusoe enslaves, splits the novel in half, and sets the plot in motion. Similarly, the little prince’s love affair and squabbles with his rose send him on an interplanetary journey. Maurice disrupts Thomas’ island idyll:

Since the discovery of his island, Thomas was perfectly happy … Thomas appreciated the solitude that he had enjoyed until the day before. It never occurred to him in the clearing to call near to him one of his parents or a friend. Happiness is an egg: alone, one is protected from everything, with two one suffocates and is disturbed. The intrusion of Maurice carved a breach in this perfection that was so round. (Déon 30, my translation)

Interestingly, the narrator describes happiness and perfection as round while the intrusion of another being threatens this peace. The broken egg image suggests the trauma of birth that splits one being into two, or the transition from puer aeternus to puer existens.

The spread in Thomas et l’infini that encapsulates this tension between self and others, finitude and infinitude, is Delessert’s surreal illustration of Thomas partially enclosed on a profusion of spherical planets. In some illustrations, his head is enclosed in a bubble while in others his head comprises the entirety of the planet. Thomas emerges from or enters the planet in the foreground through a minor insertion that resembles a sperm cell penetrating an egg. He plays with the idea of integrating himself into spherical time and detaching himself more and more from his life on Earth.

he alternative temporalities, or crip time, that Thomas experiences in his feverish dreams allow him to move back and forth between his prelapsarian paradise and his sickroom. Beauvais reads the little prince’s death as a failed attempt to restore the child to cyclical, eternal time since he has already been corrupted by adult, existential time. Déon’s rewriting less ambiguously restores the child to a circular temporality, providing a comforting fantasy for the adults Thomas leaves behind.

Works Cited

Beauvais, Clementine. The Mighty Child: Time and Power in Children’s Literature. John Benjamins, 2015.

Déon, Michel. Thomas et l’infini. Illustrated by Étienne Delessert, Gallimard, 1975.

Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de, Le Petit Prince, Reynal & Hitchcock, 1943.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Yvonne Medina is a Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow at Georgia Institute of Technology. She graduated from the University of Florida with her doctorate in English literature where she specialized in Anglophone children’s literature and critical disability studies. She holds a B.A. from Bryn Mawr College in English and French literature. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Children’s Literature in Education and Children’s Literature Quarterly.

Comments