The Arctic in Literature for Children & Young Adults

- Heidi Hansson & Maria Lindgren Leavenworth

- Feb 23, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 8, 2023

After finishing the research projects Arctic Discourses and Arctic Modernities we realized that children’s fiction set in the Arctic deserved its own study. With the anthology The Arctic in Literature for Children and Young Adults (Routledge 2020), we gathered fourteen researchers from Europe and North America to investigate how the circumpolar Arctic has been and is represented to a juvenile audience. Starting in late nineteenth-century fiction, the contributions demonstrate a myriad of meanings of the Arctic, produced by time period, by genre, and by whether the author is a visitor or someone to whom the Arctic is home. In the early examples we discuss, the Arctic is commonly presented as geographically uniform and as a setting for fantastic adventures, or as offering a temporary home for visitors. In more realistic narratives, challenges connected to particular icy landscapes and cold climates support the young protagonists’ transition into adulthood. And in contemporary fiction, the Arctic plays a central role in fiction illustrating vulnerable ecosystems and the effects of climate change.

The anthology is divided into three thematic sections. The first, “Polar History and Its Transformations,” begins with Anka Ryall’s chapter about the image of Fridtjof Nansen in comic

and graphic texts by, among others, Bjørn Ousland, Tor Bomann-Larsen, and Øystein Dolmen. The texts both build on and subvert the image of the Norwegian explorer as a polar icon. The image of the Arctic through the eyes of visitors is the focus of the next two chapters. Silje Gaupseth examines Vilhjálmur Stefánsson and Violet Irwin’s Kak, the Copper Eskimo (1924), arguing that the educational aspirations of the book conceal colonial discourses. The Snow Baby books, written by Robert E Peary, Josephine Diebitsch-Peary, and their daughter Marie Peary (published between 1901 and 1942), are discussed by Lena Aarekol who illustrates processes of mediation of the Arctic, childhood, indigeneity, and gender. The last chapter in the section, by Henning Howlid Wærp, charts changing perceptions of the polar bear in Nordic literature, corresponding to changes in perceptions of the Arctic from dangerous to threatened.

In the second section, “Indigenous and Localized Arctics,” the focus shifts to texts with ties to specific localities and indigenous perspectives, with the aim of illustrating ideological and political changes. Ingeborg Høvik’s chapter addresses the tensions between written text and images in R. M. Ballantyne’s 1857 novel Ungava, with particular

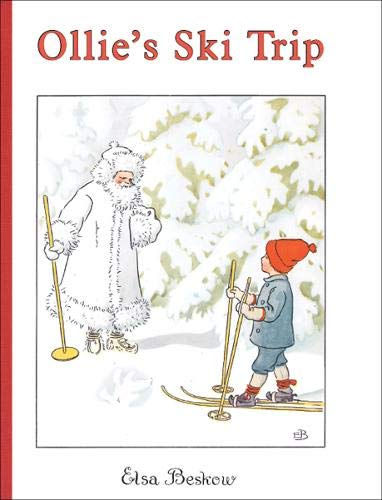

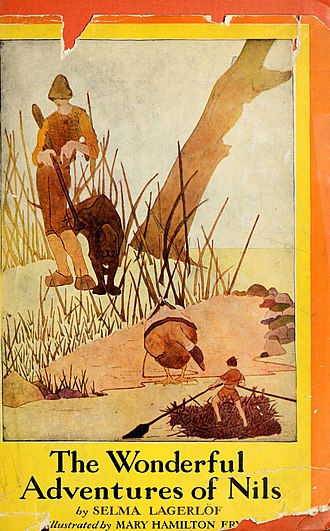

emphasis on how an imaginary space for the performance of gender is created. JoAnn Conrad analyses the journey motif in early Swedish children’s books, among them Selma Lagerlöf’s The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, Elsa Beskow’s Ollie’s Ski Trip, and Laura Fitinghoff’s Children of the Frostmoor (all originally published in 1907), showing how processes of Othering of northern landscapes and peoples illustrate and naturalize racist discourses. The following two chapters pay attention to how boundaries are interrogated in works by indigenous authors. Tiffany Johnstone discusses the Inuit writer Michael Arvaarluk Kusugak’s A Promise Is a Promise (1988; co-written with Robert Munsch) and Hide and Sneak (1992), demonstrating how boundaries between tradition and modernity are destabilized by an undermining of stereotypical notions of the Canadian Arctic. Lill Tove Fredriksen analyses how the real and the imaginary blend together to address contemporary ecological concerns in Sami author Máret Ánne Sara’s Ilmmiid gaskkas (2013) and Doaresbealde doali (2014). In the section’s last chapter, Silje Solheim Karlsen shows how specificities of Svalbard constitute both challenges and affordances in coming-of-age narratives about both girls and boys published between 1939 and 1971.

The lines between imagination and reality continue to blur in the last thematic section, “Arcticity and Imaginary Arctics.” In the first chapter, Heidi Hansson charts a course through texts

employing the Snow Queen figure, from Selina Gaye’s poem “The Maiden of the Iceberg” (1867), via Frank Barrett’s novella The Finding of the Ice Queen (1878) and Dorothy Carter’s popular novel Snow-Queen of the Air (1941), to the 2013 Disney film Frozen. Although all fantastic, the texts connect with the history of exploration, gender, and indigenous issues. Toni Lahtinen takes the Finnish story “Sampo Lappelill” (Topelius 1860) as a starting point for exploring tensions that arise between the mythical journey north and the Christianization of indigenous peoples. In an analysis of Arthur Ransome’s A Winter Holiday (1933), Johan Schimanski addresses how aspects of the Arctic are overlaid the geography of England's Lake District, and how this transposed Arctic becomes a site of gendered modernity. Kirsti Pedersen Gurholt examines how four Norwegian docudramas destabilize conventional male-centered Arctic exploits by foregrounding on the one hand the adventures of girls, on the other, domestic life. Finally, Maria Lindgren Leavenworth addresses three recent novels: Marcus Sedgwick’s Revolver (2009), Rebecca Stead’s First Light (2007), and Sarah Beth Durst’s Ice (2009). To varying degrees, the novels can be labelled speculative and emphasize how the real and imagined Arctic prevents the characters from physical and existential orientation.

Each contributor brought her or his interests and expertise to the project, but we happily had

opportunities to collaborate at workshops. In addition to being generally inspiring, these workshops made us see overlaps among individual chapters, which were then productively used in the thematic organization of the anthology. While the number of individual works analyzed in depth is necessarily limited, Heidi Hansson’s introduction functioned as a consistently evolving map throughout the process, drawing out the larger discourses we found ourselves in and establishing further connections among our ideas. Prefacing the sections, the introduction comprehensively outlines how the Arctic has been and is imagined; what function it has filled/been made to fill in different contexts and periods, and how continued work is necessary. “[C]ultural representations,” Hansson argues, “have important impacts on how the Arctic is understood and, in turn, influence the level of engagement in Arctic concerns, including indigenous questions, sustainable development and climate change” (2). The Arctic has migrated from its stereotypical peripheral position and is beginning to be understood as a globally valuable but also vulnerable area. Hopefully, the anthology inspires further forays into complex past and present representations, and help keep the Arctic central.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Heidi Hansson is Professor of English Literature at the Department of Language Studies, Umeå University, Sweden. In the last few years, her research has concerned the representation of the Arctic and the far North in travel writing, fiction and popular culture from the late eighteenth century onwards. A particular field of study has been gendered representations and approaches to the Arctic in both comic and serious material.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Maria Lindgren Leavenworth is Professor of Modern English Literature at the Department of Language Studies, Umeå University, Sweden. Her research connected to the north and the Arctic has addressed 19th-century travel writers Selina Bunbury, Bayard Taylor and S. H. Kent, as well as speculative fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin, Dan Simmons, Michelle Paver, and Julie Bertagna.

Comments